Health

Anesthesia as Accessibility: Sleep Dentistry’s Quiet Public Health Impact

For decades, oral care has been treated as a matter of private responsibility—brushing, flossing, scheduling six-month checkups. Yet lurking beneath these routine prescriptions is a quieter, systemic challenge: millions of people avoid the dentist not because they cannot afford it, but because they cannot face it. Dental anxiety, long dismissed as an individual weakness, has quietly become a collective public health barrier. And here, sleep dentistry emerges not just as a luxury, but as an answer to dental anxiety—a form of accessibility that reframes sedation as equity.

The Hidden Epidemic of Dental Anxiety

Dental anxiety is not rare. Studies estimate that between 9% and 20% of adults experience significant dental fear, while a smaller but still impactful percentage suffer from outright phobia. This translates into missed appointments, delayed treatments, and avoidable oral health complications that ripple outward into systemic health. Untreated cavities escalate into infections; periodontal disease correlates with diabetes and cardiovascular issues. The cost is not only personal—it is societal.

What looks like an individual fear in fact multiplies into a public health burden. Anxiety leads to avoidance, avoidance leads to deterioration, and deterioration demands more complex, invasive, and expensive interventions down the line. Sleep dentistry, by lowering the barrier of fear, interrupts this cycle before damage spirals into disability.

Sedation as a Form of Accessibility

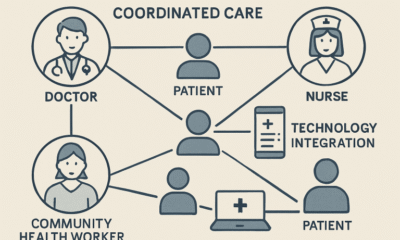

We often think of accessibility in physical terms: ramps for wheelchairs, braille signage, widened doorways. Yet accessibility is also psychological. If fear prevents patients from stepping into a clinic, then the dental chair is as inaccessible as a staircase without a ramp. By offering patients the option to rest through their procedures, sleep dentistry transforms the experience into one they can endure, sometimes even welcome.

In this sense, anesthesia is not simply a pharmacological intervention. It is an equalizer. It gives the anxious, the phobic, and those with special needs the same opportunity for oral health as those who sit calmly through the sound of a drill. For a patient who has avoided the dentist for decades, the availability of sedation is not about convenience—it is about survival.

The Economics of Fear

Public health systems often weigh the cost of sedation against necessity, framing it as an optional extra rather than a core service. Yet the economics of fear tell a different story. Patients who avoid preventive care eventually present with more severe disease, requiring complex treatments that burden both healthcare systems and families.

Sleep dentistry, when reframed as prevention rather than indulgence, becomes a cost-saving measure. It draws patients back into the system earlier, when interventions are simpler, faster, and cheaper. The cost of sedating a patient for a cleaning or a filling is far less than the surgical extraction of multiple teeth or the systemic consequences of untreated infection.

Anxiety and Inequality

Dental anxiety is not evenly distributed. Research shows higher prevalence in populations already marked by inequality—women, individuals with lower socioeconomic status, people with disabilities, and survivors of trauma. For these groups, the threshold of fear is amplified by histories of vulnerability and mistrust in medical settings.

Sleep dentistry thus has a quiet social justice dimension. By offering sedation, clinics signal recognition that oral health equity requires more than affordability—it requires compassion, and the tools to overcome barriers that are as real as any locked door. The answer to dental anxiety here is not judgment but adaptation.

Ethical Dimensions of Comfort

Critics sometimes argue that sedation only masks the problem rather than solving it. Shouldn’t we be helping patients confront their fear rather than drifting into unconsciousness? Yet this reasoning risks moralizing comfort. Forcing exposure therapy in the dental chair ignores the immediacy of pain, infection, and declining health.

Sleep dentistry does not prevent patients from also pursuing psychological strategies for long-term anxiety management. Instead, it ensures they do not have to sacrifice their health while waiting to “be brave.” In ethics, autonomy is honored not only through informed consent but through choice—and sedation expands choice for those who otherwise have none.

A Public Health Lens for the Future

To recognize sleep dentistry as public health rather than private luxury is to widen the definition of accessibility itself. In the future, dental policies could integrate sedation as part of subsidized care for high-risk groups. Training more dentists in sedation techniques could be framed as workforce development, not boutique specialization. Outreach campaigns could normalize sleep dentistry, reframing it not as a weakness but as a legitimate pathway to care.

Indeed, sleep dentistry may be dentistry’s quietest revolution—not in how teeth are drilled or crowns are placed, but in how doors are opened for patients who previously stood outside.

Equity in Silence

When anesthesia is seen not only as a drug but as a bridge, its role in dentistry expands beyond comfort. It becomes accessibility, equity, and prevention rolled into one. Sleep dentistry is not the abandonment of courage, but the recognition that health should not be contingent upon it.

In the end, perhaps the quiet hum of a patient breathing peacefully under sedation is not just the sound of relief—it is the sound of public health working as it should: inclusively, compassionately, and without judgment. In that silence, we hear the future of dentistry.